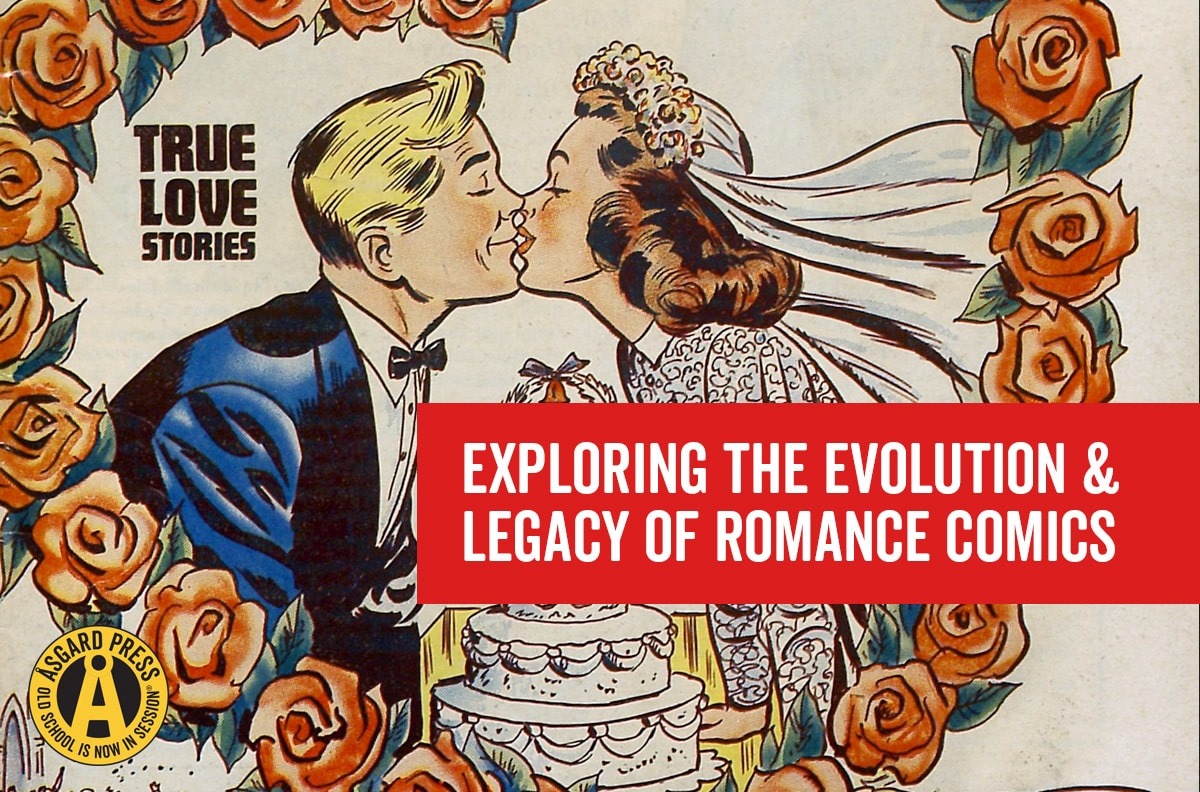

Romance Comics: Exploring the Evolution and Legacy

The emergence of romance comics in the post-World War II era marked a significant departure from the dominance of superhero narratives within the comic book industry. As society underwent profound social and cultural shifts, comic readers sought forms of escapism that resonated with their more adult experiences of love and relationships. Romance comics quickly gained traction, however, beneath the surface allure of these narratives lay a portrayal of gender roles and relationships steeped in patriarchal values and societal norms. This article delves into the evolution and legacy of romance comics, exploring their cultural impact, portrayal of women, and eventual transformation in response to changing societal attitudes.

Adult Comic Readers Look Beyond Superheroes

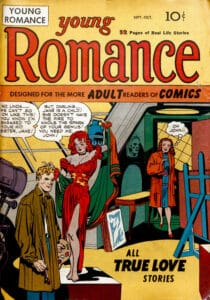

In the era following World War II, the comic book industry was searching for a new mainstay for an increasingly adult readership. Superheroes were losing popularity among this new demographic, with readers craving novel escapism during a time of social and cultural change. In 1947, the romance comic genre was introduced by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby of Crestwood Publications, through the launch of Young Romance, “designed for the more adult readers of comics.”

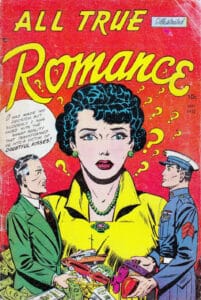

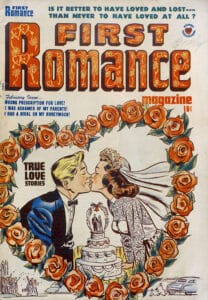

With the publication of Young Romance in 1947, the genre of romantic comics soared in popularity. By the 1950s, most publishers carried at least one romance title. These comics were particularly appealing to young women, who were themselves experiencing their first crushes and love entanglements. Romance comics frequently dealt with themes such as heartbreak, divorce, infidelity, even crime, providing readers with an often-salacious form of escapism.

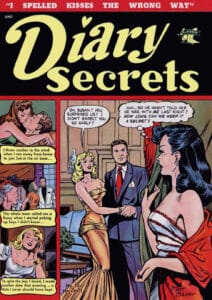

The romance genre of comics took inspiration from pulp and true confession magazines, newspaper comic serials, and radio soap operas to build storylines that were sophisticated and adult in nature. Romance comics aspired to an aura of realism presented through first-person narration and contemporary artwork depicting people and scenery as they appeared during the era of publication. The characters in these comics were older than those of earlier teen publications to align with adult readers.

Romance Comics Reflected Societal Expectations of Women

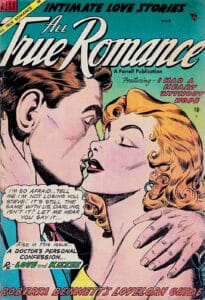

Romance comics of the postwar era displayed an idealized version of American life in which women were expected to settle down to marriage and motherhood. Female characters who were faced with choosing between independence and domesticity often experienced a series of disappointments before ultimately capitulating to the status quo. Behaviors such as promiscuity and ambition were presented as cautionary tales resolved by conforming to contemporary values.

Career ambition was particularly discouraged by the storylines of romance comics. Intelligent women were portrayed as undesirable to men, and women engaged in careers were presented as unable to sustain a successful relationship due to the complications a job brought to their love life. A popular story trope of this genre was that of an independent working woman giving up her career to pursue a more noble path of true love and domestic bliss.

Another popular story trope of romance comics involved women faced with choosing between two suitors. Often, one suitor was a “bad boy” while the other was inevitably a solid, stable man. The exciting, non-conformist choice threatened heartbreak while the dull, respectable choice promised safety and security. Teen girls and young women could harmlessly explore their “bad boy” interests through these stories, which sometimes even saw the bad boys redeemed at the end.

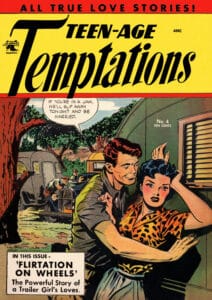

Although romance comics tended to adhere to contemporary social norms of the era, such as marriage and conformity, some issues explored more adventurous female characters. Women in these stories listened to rock and roll and challenged conventional notions by defying the authority of men. Teen rebellion was often presented as a readership draw and was dismissed as juvenile at a time when horror and crime comics were raising more concern among parents.

The Effect of the Comics Code Authority

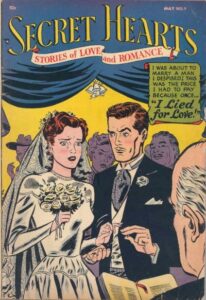

In 1954, the Comics Code Authority was formed by the industry in response to Senate hearings on the increase in juvenile delinquency, following the publication of psychiatrist Fredric Wertham’s book Seduction of the Innocent. Wertham argued that comic books were a major contributor to troubled youth in America. As a result, comic publishers began self-regulating their content to avoid corrupting young people. Although originally focused on crime and horror comics, romance comics eventually conformed to these new standards as well.

As a result of the implementation of Comics Code Authority standards, romance comics became even more focused on a traditional, patriarchal approach to love and relationships. Storylines eliminated anything salacious or controversial and painted an even more conservative picture of gender roles, female behavior, and attitudes toward sex. As America entered the 1960s, however, a cultural revolution that redefined women’s place in society contributed to the decline of the romance comic genre.

Romance Comics Create New Opportunities for Women in the Comics Industry

Although romance comics promoted a highly misogynistic standard of behavior that often pigeonholed women into secondary roles in society, behind the scenes the genre affected real change for women in the comics industry. With the advent of female-centered titles came more opportunities for women artists, writers, and editors. Women such as Zena Brody, the first female comic editor, and Lily Renée, an early Golden Age comic artist, broke ground in a mostly male-dominated field.

When judged by the social and cultural values of today, early romance comics ooze misogyny and outdated attitudes toward women and relationships. But these publications serve a purpose as cultural artifacts and important resources for understanding the times in which they were written. Because the genre had the goal of appearing as realistic as possible, these comics help us understand the evolution of the role of women in society, especially when compared to the more liberated female comic characters of the present day.

Despite changing attitudes toward relationships and gender roles, romance comics remain popular among many readers today. Like many other comic genres, original copies of romance comics can be quite valuable and collectible. Many readers find ironic humor in the pages of old tales of love, as well as in the accompanying advertising, and some publishers have even recreated romance issues with new, albeit snarky, dialog. If understanding our past enlightens our present, then romance comics may have much to teach us.

This essay originally appeared as commentary in our 2024 Vintage Romance Comics Calendar.